Originally published in The Antiques Trade Gazette.

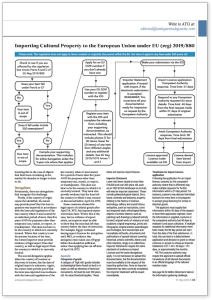

New regulations on importing cultural goods are looming and could mean significant challenges for the trade, writes Ivan Macquisten.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

On June 28 a major change comes to the international art and antiques market.

The European Union will enforce its new import licensing regulation (Regulation (EU 2019/880), imposing significant challenges on many people importing cultural goods into the EU. This will impact sales to the EU from the UK, US, and Far East as a result.

The law will not affect everyone – it will not apply to anything that originated in the EU, nor to anything under 200 years old, for example – but for those who will have to navigate its terms, the effects are likely to prove far-reaching.

It’s worth bearing in mind that the regulation will include more cultural goods within its scope as the years pass. While this year it capturesobjects dating from 1825 (or 1775 for certain categories of objects), in 20 years’ time it will capture objects dating to 1845 and so on.

The regulation passed into law in 2019, aiming to prevent stolen or trafficked items from entering the EU, particularly objects that might have helped fund terrorism.

Art and antiques market representatives have been negotiating with the European Commission (EC) for years over how to interpret the regulation’s requirements. The EC has issued several guidance papers, but significant questions remain.

So, who and what will the law affect?

- It applies only to a range of goods of non-EU origin.

- The range in scope is set out under Parts A, B and C of the Regulation’s categorisation Annex. (See next section and Appendix.)

- The import application process must be completed by the importing owner of the goods, even where that is the private client or customer.

- The import process can be conducted only by registering with the EU’s ICG (Customs’ digital registration system).

Cultural goods

In brief, the cultural goods categories applying to the regulation stipulate the following:

Part A: No cultural good illegally removed from the country in which it was created or discovered may be imported into the EU.

Part B: Cultural goods listed in this section of any value, aged more than 250 years, need an Import Licence to be imported into the EU. (See 2019/880 Article 4.)

Part C: Cultural goods listed in this section individually valued at more than €18,000 (including all associated costs, such as sales taxes, insurance, packing and shipping) and aged over 200 years must be subject to a completed Importer Statement before EU import. (See 2019/880 Article 5)

Challenges under the regulation

In summary, the chief challenges are as follows:

- Permission for import may often require applicants to provide what may often be non-existent evidence to prove the legal export from the country in which a cultural object was created or discovered.

- Standards of proof way above the norm.

- Exposure of the individual importer to unreasonable legal risk.

- Uncertainty over related delays.

- Uncertainty over related costs, all of which must be borne by the importer regardless of their cause.

- Only the EU-based owner of the goods may complete the process.

Pinch points

These arise at various stages of the process, leading to challenges such as (but not limited to) the following:

- Those selling goods in scope to private buyers in the EU must ask themselves: how likely is my client to complete the import process themselves?

- As an importer, how do I apply for an EU EORI (Economic Operators Registration and Identification) number, the essential first step? Without an EU EORI number the potential importer will not be able to register with ICG and embark on the application process.

- The importing owner must sign a declaration taking legal liability (on pain of criminal prosecution) for the veracity of documents associated with the cultural good they wish to import. This includes responsibility for any information relating to previous owners, even where they have no means of checking that those documents are accurate (which will be the case most of the time).

- How will an importer know which historic export laws apply to the object they wish to import to the EU when no comprehensive database of such laws exists?

Wider issues surround goods that are currently imported under Temporary Admission rules for events such as fairs. If sold to an EU buyer, they must undergo the complete import process anyway.

Wider issues surround goods that are currently imported under Temporary Admission rules for events such as fairs. If sold to an EU buyer, they must undergo the complete import process anyway.

Recent advice from the EC acknowledges that sensitive personal data about previous owners protected by EU GDPR rules would remain confidential but will still have to be included in the submission. However, if that information is not available because, in keeping with GDPR requirements, it has not been passed on during earlier transactions, it will not be available to pass on during the current import process.

Articles 70 and 71 of the EU Customs Code apply to the €18,000 value threshold, above which relevant goods require an importer statement. However, as the valuation includes associated costs such as buyer’s premium, packing, shipping, and insurance costs, it may prove difficult to decide whether an object is in scope or not.

Equally challenging is that the Import Licensing process could take up to five months, considering the submission of documents, further requests for information from Customs or the competent authorities, analysis of the application and the issuing of a decision (approval or denial).

It is still not clear how cultural goods, whatever their origin, that have already circulated freely within the EU will be treated on their return there. The regulation appears to allow for them to return within three years without the need for a new licence or Importer Statement. However, guidance does not say whether this applies to cultural goods that return to a different EU country and owner from those from whom they were originally exported.

This relates to how Returned Goods relief is applied in the EU compared with the UK; for instance, where the exporter and the importer must be the same person.

Uncertainty also remains over what qualifies as sufficient documentation for compliance.

Current guidance appears to advise that a declaration under oath of a third party regarding the legal export of a cultural good might be acceptable in the absence of relevant documents to prove this. It also appears to advise that a detailed auction or exhibition catalogue description along with an identifying photograph might be sufficient evidence of original legal export to permit the issuing of a licence or acceptance of an Importer Statement.

Despite this, however, earlier conflicting advice may mean that the current guidance does not signify what it appears to advise.

Import Licence

The importer (owner) must sign a legal declaration that the item in question was legally exported from its country of origin under the local law of the time, whenever that was. This means that the importer must know which country was the country of origin when the original export took place and what the local law was at the time (or that none existed).

The importer (owner) must sign a legal declaration that the item in question was legally exported from its country of origin under the local law of the time, whenever that was. This means that the importer must know which country was the country of origin when the original export took place and what the local law was at the time (or that none existed).

The likelihood of the owner knowing this in the case of objects that have been circulating in the market for decades or longer is close to nil.

Derogations

Fortunately, there are derogations that recognise this challenge.

Firstly, if the country of origin cannot be identified, the owner may provide proof that the item in question was exported in accordance with the laws and regulations of the last country where it was located for an unbroken period of more than five years AND for purposes other than temporary use, transit, re-export, or transhipment. This does not have to be the country in which is it currently located. Where that country is not the present location of the item, the owner/importer must provide evidence of legal export from that country, as well as legal export from the country in which it is currently located.

The second derogation applies when the country of creation or discovery is known, but the date of original export is unknown. Again, the owner must provide proof that the item was exported in accordance with the laws and regulations of the last country where it was located for a period of more than five years AND for purposes other than temporary use, transit, re-export, or transhipment. This does not have to be the country in which it is currently located. They must also provide evidence that the item left the country in which it was created or discovered before April 24, 1972. Some countries allowed for legal export of cultural goods after April 24, 1972, but imposed export restrictions later. Where this is the case, but no evidence of export exists, an importer must be able to show that the item had left that country before the date of restriction. For example, Egypt continued issuing export licences for antiquities until 1983, so evidence that antiquities were taken out of Egypt before this should be sufficient, rather than applying the cut-off date of April 24, 1972.

Appendix

Categories of goods

A category of ‘high risk’ goods includes archaeological items found on land or in water, as well as elements of historical monuments. All must be over 250 years old. No value threshold applies. These items will need an import licence.

Importer Statement

Lower risk items valued at more than €18,000 and over 200 years old, such as an 1820 British landscape or portrait, will need an importer statement. These include palaeontological objects, flora, fauna, minerals and anatomy; property relating to the history of science, technology, military and social history; antiquities, such as inscriptions, coins and engraved seals; ethnological items; objects of artistic interest, such as paintings and drawings produced entirely by hand; original works of statuary art and sculpture; original engravings, prints and lithographs; original artistic assemblages and montages; rare manuscripts and incunabula; old books, documents and publications of special interest covering historical, artistic scientific, literary and other interests, singly or in collections. Importer Statements require the same standards of evidence as Import Licences and the same derogations apply. It is not necessary to upload this documentation, but the documentation must be available at the request of the importing authorities. Once an Importer Statement has been correctly completed, the Importer Statement will be issued immediately.

Timeframe for Import Licence application

Following the application for an import licence, customs (or the competent authority where that is different) may make multiple requests for further information within a 21-day period. For instance, customs may demand individual licences for every item or be prepared to accept group licensing for similar or identical goods.

The applicant must supply that information within 40 days of the request or have their application rejected. Once the information is supplied, customs or the competent authority has 90 days to evaluate it and issue a decision. If multiple requests for additional information have been made, the 90-day period will start from the date of the final submission. In total, this can lead to a delay between application and decision to grant or refuse a licence or accept or refuse an Importer Statement of 21 + 40 + 90 days = 151 days, or approximately five months. NB The customs authority may require the applicant to upload official translations of all relevant documents in an official language of the relevant member state.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Reproduced with permission of the author.